Le projet de loi sur les lanceurs d'alerte au Sénégal : une réforme audacieuse ou l'aveu d'une défaillance systémique ? (Par Modou BEYE)

“Truth is a path that is not afraid of solitude.” This quote from Confucius resonates with particular acuity in democracies struggling to regulate themselves. In Senegal, Bill No. 13/2025 on whistleblowers is a major legislative initiative, presented as a pillar of transparency. However, its main feature, a 10% bonus, raises fundamental questions about the health of public governance.

Senegal already has a legislative framework encouraging whistleblowing.

Article 7.3 of Law No. 2012-22 of 27 December 2012, establishing the code of transparency in the management of public finances, provides that "denunciations... are provided for against all those who, whether elected officials or public agents, have violated the rules governing the

public funds”. It goes even further by criminally sanctioning the non-

denunciation by a public official who has knowledge of it.

But this provision, although strong on paper, was clearly not enough to

curb illicit practices. Reports from oversight bodies, including the Court of Auditors and the OFNAC (National Office for the Fight against Fraud and Corruption), have often highlighted dysfunctions, embezzlement, and a lack of follow-up to recommendations. These institutions, despite their mandate, have sometimes encountered resistance, a lack of resources, or a lack of real political will to bring cases to a conclusion.

Bill 13/2025 steps into this breach by proposing a monetization of civic acts. As the American philosopher points out,

Michael Sandel in "What Money Can't Buy"1, transforming a duty

moral in commercial transactions can have perverse effects. This bonus, far from being a simple encouragement, can be interpreted as an admission of bankruptcy

institutional: that of a State which, despite the existence of laws and institutions of

control, is forced to outsource its vigilance and pay its citizens for what its own bodies have failed to accomplish, and for which they are generously remunerated.

The question is therefore this: Is the whistleblower bill, with its financial reward, a real step forward for Senegalese governance or a symptom of a systemic deficiency where the State relies on its citizens to compensate for its own weaknesses?

I. The promises of democratic progress

Bill No. 13/2025, although the subject of criticism, constitutes a significant step forward for the Senegalese legal framework by establishing a status and protection for whistleblowers.

• Legal recognition of whistleblower status: The text

establishes a clear legal framework for people who report facts

serious, with a guarantee of anonymity and a prohibition of reprisals.

• The creation of a Special Recovery Fund: This fund allows the

both to fund social projects and to reward whistleblowers.

• An incentive financial reward: The 10% bonus is a first

in French-speaking Africa, which is likely to stimulate reporting in

a context of institutional mistrust.

1 Michael Sandel, What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of the Market, trans. Christophe Jaquet,

Paris, Seuil, 2014.

• A framework for the alert field: The text excludes information

protected by sensitive secrets, thus preserving a balance between

transparency and national security.

II. The flaws and limitations of the proposed system

Despite these positive points, a closer analysis of the bill reveals

flaws and limitations that could compromise its effectiveness and scope,

particularly with regard to international standards.

1. Scope of application: selective and restrictive protection

Although Bill No. 13/2025 mentions the concept of "prejudice to the interest

general,” this reference does not mean that the scope of the law is broad.

On the contrary, it is deliberately selective and restrictive, as the protection only applies to financial crimes and offenses that are listed in a restrictive manner.

The problem is that if a whistleblower reports a major risk to public health or the environment that is not directly related to financial fraud (for example, a medical product defect or groundwater pollution without embezzlement), they are not explicitly protected. This approach departs from more comprehensive legislation, such as the 2019 European Directive, which explicitly covers a wide range of areas of public interest.

Proposal to rewrite Article 1 To address this flaw, Article 1 could be rewritten to include a broader scope, explicitly incorporating non-financial areas of general interest.

• Original text: “A whistleblower is a natural person who...

reports... information relating to the commission or attempted commission of

commission of acts relating to a crime or financial offense, a threat or

damage to the general interest, a violation or an attempt to conceal a violation affecting the management of finances both in the sector

both public and private.

• Rewrite proposal: “A whistleblower is a natural person

who, in good faith, reports, communicates or discloses information relating to

to a crime, an offense, a threat or harm to the general interest. This

includes, but is not limited to, environmental, health and safety impacts

public, as well as violations of the law or regulations relating to

financial management in the public and private sectors.

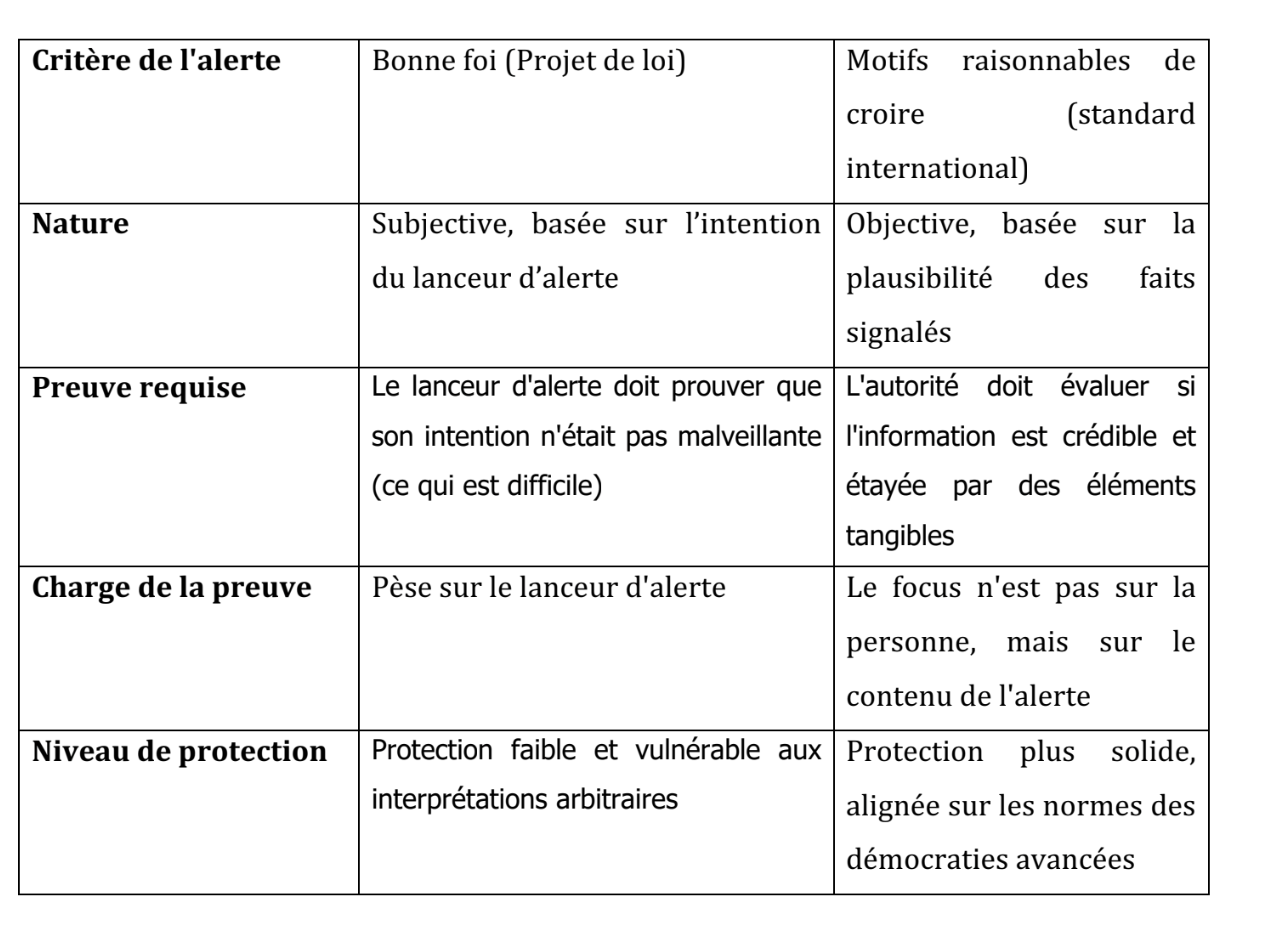

2. Condition of “good faith” too subjective

The bill classifies the whistleblower as a person acting in "good faith." This notion, based on intent, can be interpreted arbitrarily. International standards recommend relying on "reasonable grounds for

believe ".

Proposal to rewrite Article 1

To align with international standards, Article 1 could be amended to

replacing the criterion of “good faith” with that of “reasonable grounds to believe

".

• Original text : “A whistleblower is a natural person who...

reports... in good faith information relating to the commission or the

attempted commission of acts relating to a crime or financial offense... »

• Rewrite proposal : “A whistleblower is a natural person

who, having reasonable grounds to believe in the truth of the facts, reports,

communicates or discloses information... »

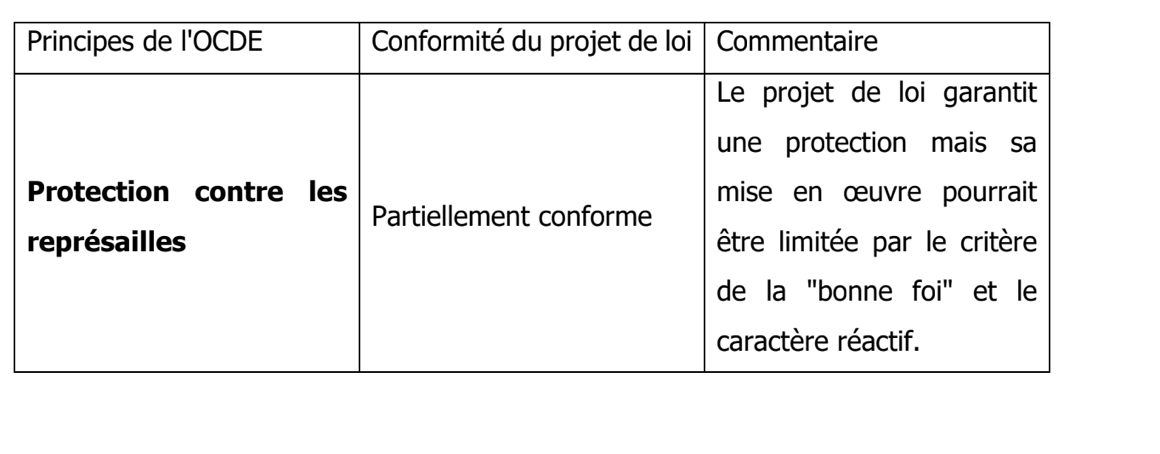

3. Insufficient protection of facilitators

The protection extended to facilitators by Article 2 is crucial, but it does not resolve

not entirely address the issue of protection for facilitators. The bill protects "natural persons or legal entities under private non-profit law who provide help and assistance to a whistleblower." It also protects relatives and legal entities linked to the whistleblower. However, this protection

East :

• Reactive and not proactive : The text protects people or

entities after they have suffered "violence, threats, intimidation or

retaliation". It does not provide a clear legal status or framework for action for the

role of "facilitator" upstream. For example, a journalist or a lawyer who

receives an alert does not have a legal status which governs its work

verification and disclosure, which exposes the individual to legal risks.

The law focuses on the consequences (retaliation) rather than the

securing the act itself.

• Linked to a restrictive scope of application : The protection of Article 2 is

dependent on the scope of Article 1. If a journalist receives a

alert that does not concern a case of corruption or financial crime, it does not

would not be protected by law in the event of retaliation.

Proposal to rewrite Article 2 and a new Article

To strengthen the protection of facilitators, it is necessary to clarify their status and make protection more proactive and explicit.

• Original text of Article 2 : “Any

natural or legal person having suffered direct or indirect reprisals,

due to professional or family ties, of a whistleblower.

• Proposal to rewrite Article 2:

Article 2. Natural persons and

following morals, which assist a whistleblower:

1. Facilitators, whether individuals or legal entities, who provide legal, media or logistical assistance in the reporting or disclosure process.

2. Those close to the whistleblower, including family members, who are at risk of retaliation or harm.

3. Legal entities controlled by the whistleblower or with which he has a professional connection.

• Proposal for a new Article 2 bis:

Article 2a. Journalists and lawyers who, in the course of their activities

professionals, receive information from a whistleblower are presumed to act

in good faith and cannot be criminally prosecuted for the simple fact of

disclosure, if this takes place in compliance with the conditions set out in this law.

Explanation: The use of the criterion of "good faith" for the journalist is part of

in a logic of professional ethics. It protects the journalist or lawyer by presuming that they have done their due diligence and that they have not acted out of pure malice. This approach protects the role of the press as a "watchdog" without granting it total impunity, while distinguishing itself from the subjective criterion used for the whistleblower.

4. Overly rigid reporting channels

The bill establishes a hierarchy in reporting channels, which can hamper disclosure and expose the whistleblower to risks.

• Priority to internal routes: Article 4 of the draft law indicates that the launcher

alert can make a report internally or externally as soon as

that he believes that it is possible to remedy it effectively by these means and that he does not

is not exposed to reprisals. However, Article 5 and Article 6 insist on

internal reporting to a "structure referent". This approach is

problematic in a context where institutions are weak or potentially complicit in the facts denounced.

• Limited public disclosure : The right to public disclosure, a

crucial last resort mechanism, is only permitted under conditions

very strict and after specific deadlines. The whistleblower must wait

the expiry of a period (two months for the internal referent, three months for

the anti-corruption body) and note "inaction" in order to be able to disclose

publicly his alert.

• Divergence with international standards: The obligation to wait

inaction by the authorities may allow the person in question to

conceal or destroy evidence during this period.

Proposal to rewrite Article 8

To make reporting channels more flexible, Article 8 could be amended to provide

more flexibility for the whistleblower, drawing inspiration from international standards.

• Original text : “Upon expiry of the time limits, the whistleblower, who

finds inaction, is free to publicly disclose the information

transmitted as part of the report, if there are risks of concealment

or destruction of evidence."

• Rewrite proposal : “The whistleblower may carry out a

public disclosure if he has reasonable grounds to believe that his report

has not been treated, that there is an imminent or irreversible danger to the interest

general, or that he risks reprisals by using internal channels or

external.

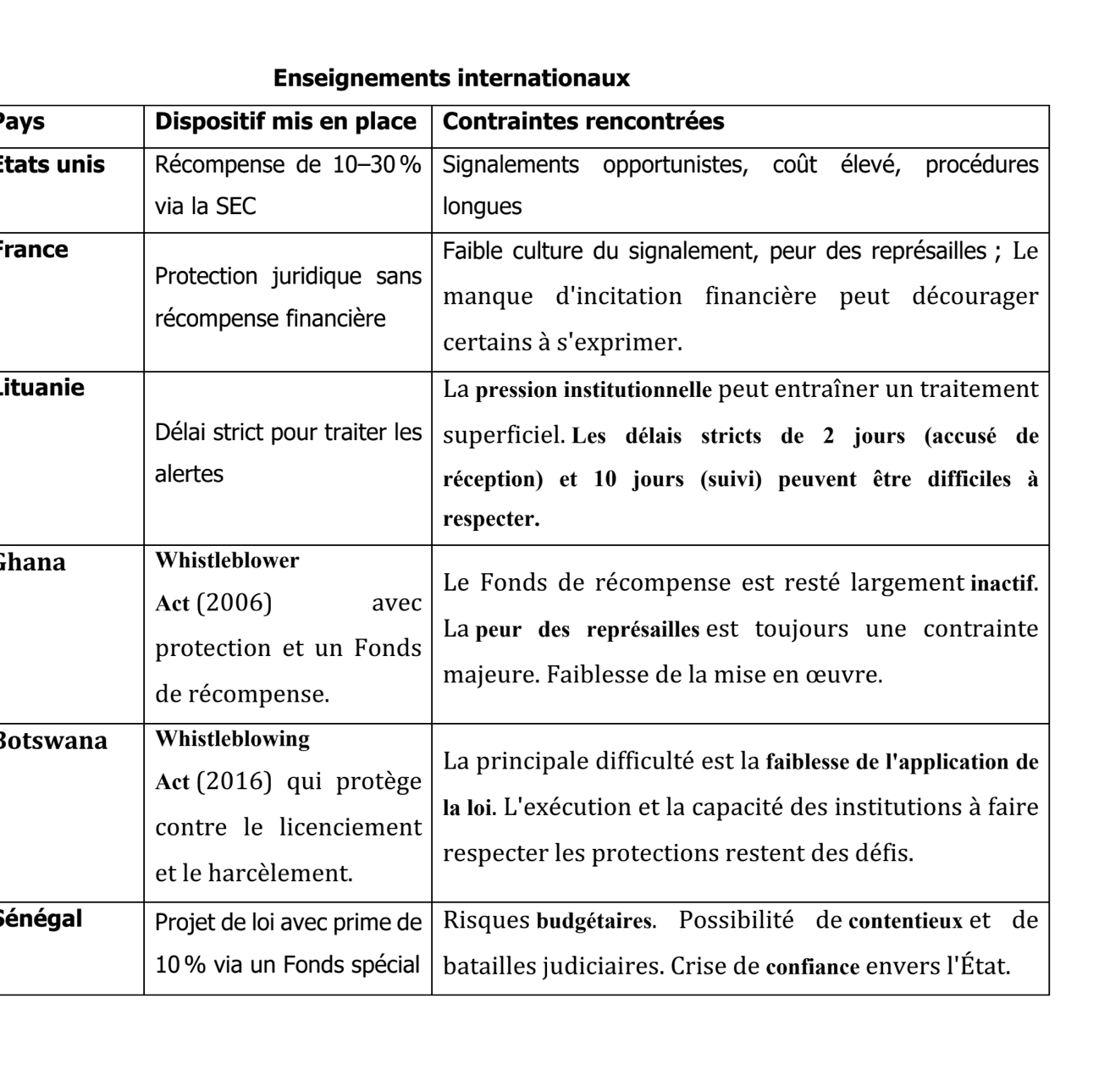

III. A comparative overview: Senegal tested by international standards

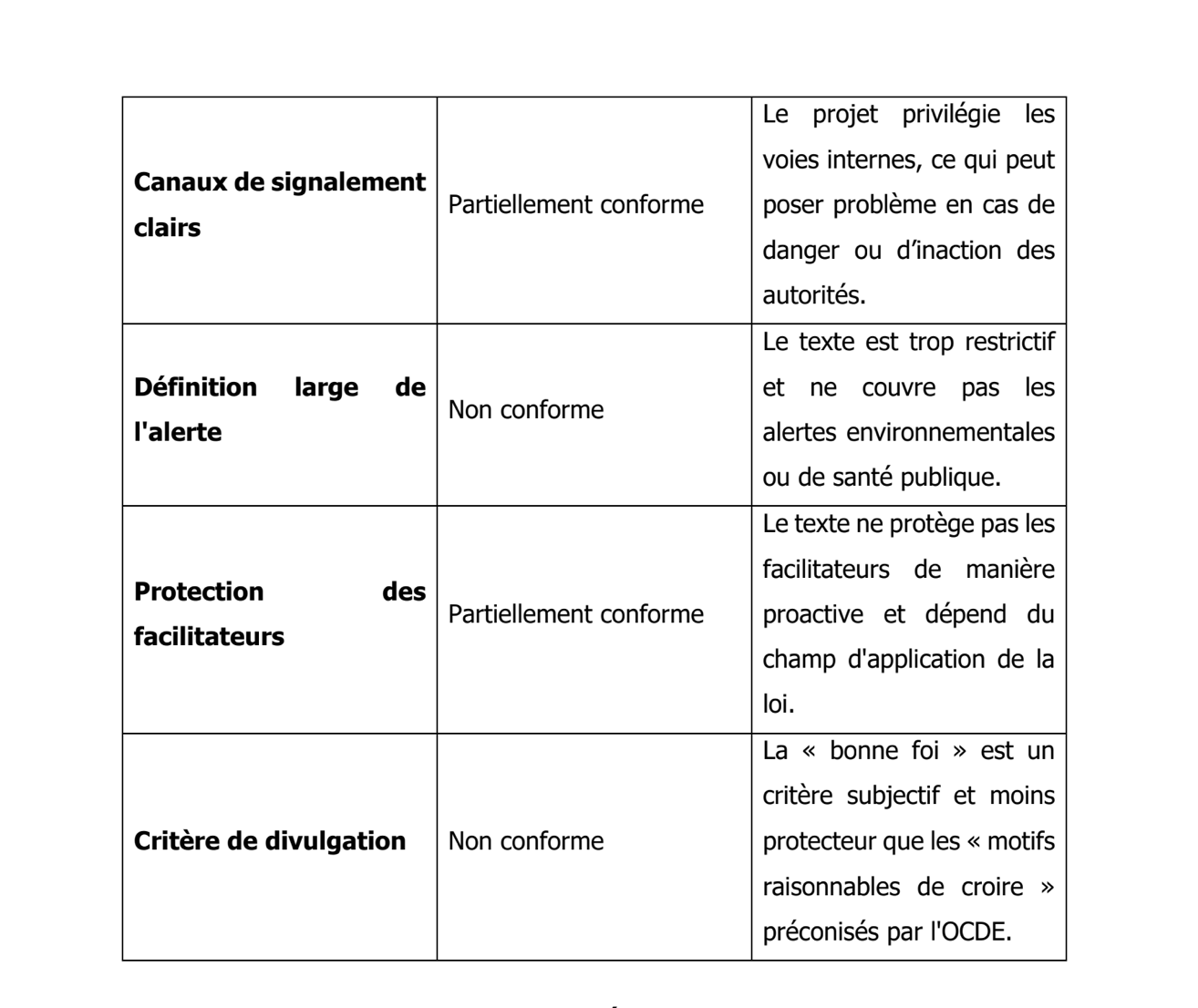

IV. Multidimensional risks for the State

The adoption of this law, even if it is beneficial, exposes the State to risks that it

must anticipate and manage.

V. Recommendations for strengthening the system

For the bill to be fully effective and compliant with standards

international, it must be strengthened on several levels, taking into account the identified risks.

1. On the legal level:

o Broaden the scope : Do not limit yourself to corruption and

to economic crimes, but include all attacks on the interest

general (environment, health, human rights, etc.).

o Replace “good faith” with “reasonable grounds to believe” : This is a crucial change for better protection of the whistleblower, in alignment with international standards, because it is based on the objectivity of the information rather than on subjective intention.

o Strengthen the protection of facilitators : Extend the protection of facilitators by providing them with a clear legal status and a framework for action for the role of “facilitator” upstream.

o Recognize the right to public disclosure : Provide for the possibility

for the whistleblower to publicly disclose the information in case

of imminent danger or proven inaction by the authorities via the channels

internal.

2. On the institutional level :

o Ensure the independence of the alert processing authority :

A dedicated entity, with sufficient resources and real autonomy, is essential to ensure the credibility and effectiveness of the system.

o Establish a monitoring and evaluation mechanism : It is essential to measure the impact of alerts and publish annual reports on reports and the results obtained to ensure accountability.

3. On the Budgetary and Operational levels :

o Indirect costs : Include the costs of premiums and investigations in the State budget and provide provisions for litigation risks in order to ensure the financial viability of the system.

o Invest in a secure digital system: Implement

a reliable and confidential platform for filing and processing

alerts.

4. On the Strategic and Ethical level :

o Place the law in a broader strategic vision : The law must not be a simple reaction tool, but be integrated into a global risk governance strategy focused on crisis prevention, institutional coordination, investment in transparency and the modernization of control tools.

o Strengthening the culture of public ethics : Beyond whistleblowing mechanisms, it is essential to cultivate an environment where integrity and accountability are the norms, thus making whistleblowing less necessary.

VI. Conclusion : A high-risk but necessary bet

Bill 13/2025 marks a democratic step forward for Senegal, but its success depends on its ability to overcome its structural weaknesses. Financial rewards, while innovative, cannot be the sole pillar of a transparency policy. To be fully effective, they must be accompanied by a structural reform of oversight institutions. In short, monetizing civic action is a high-risk gamble, but one that could generate great promise if the architecture of this mechanism is designed with rigor and integrity.

Modou BEYE, Treasury Inspector, Director of Finance and Accounting of SAFRU SA

Commentaires (1)

Savez-vous quand est-ce que les insultes ont commencé sur les réseaux sociaux ? C’était le moment où on pouvait gagner de l’argent (monétiser) par des nombreuses vues ! Les gens étaient prêts à dire, faire, du n’importe quoi pourvu qu’il gagnent de l’argent ! C’est cela qui va se passer avec ce projet de loi, si il passe !! Pour moi, c’est un mauvais projet de loi ! On va se mettre à accuser de honnêtes gens, sans preuves et pour se faire soi-même de l’argent !! C’est immoral !!

Un état, qui devrait avoir les moyens pour contrôler ses agents, se voit obligé de passer par ses citoyens, pour des délations, n’est pas un état sérieux !! Je suis moralement contre ces projets de lois !!

Participer à la Discussion