Architecture africaine, mémoire effacée d’un génie vernaculaire

What if concrete were just one episode in a much longer, denser, more deeply rooted history? What if African architecture did not find its origins in the grid plans of colonial urban planners, but in the palm of a mud brick mason, in the gesture of a Dogon blacksmith sculpting a lintel, or in the gaze of a Toucouleur child recognizing the shapes of his memory in those of a raw earth granary?

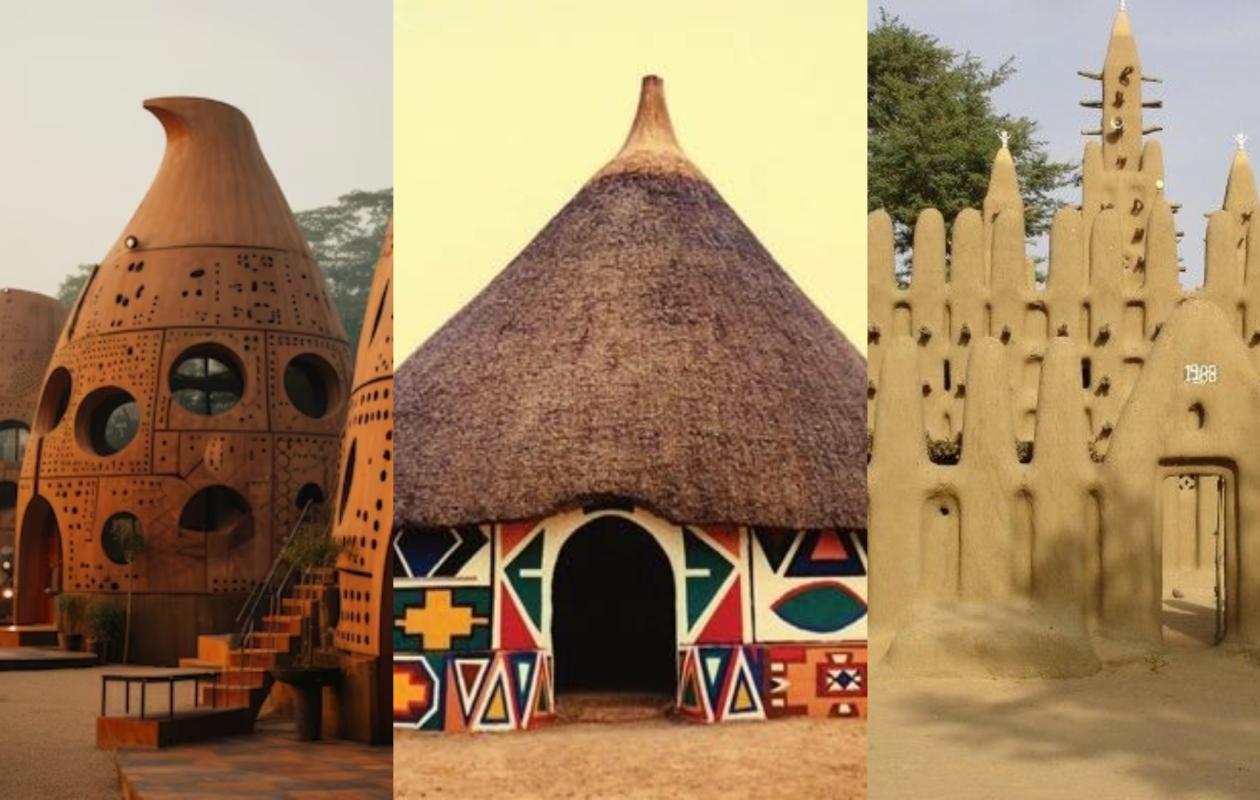

Before the word “architecture” was confined to academic grids or international competitions, it was experienced here as a breath of fresh air. People built with the earth, not against it. Bassari dwellings blended into the slope of the hills, Serer huts opened their conical roofs to the sky, Mossi granaries took the form of function, without ever giving in to the superfluous. Ingenuity lay in adaptation: natural freshness, bio-sourced materials, short supply chains ahead of their time. These forms were not poverty in disguise, but built wisdom.

And yet, these architectures have gradually become invisible. Neither cited in school textbooks nor integrated into urban policies, they have been relegated to ethnography or folklore. Worse still, they are sometimes perceived as relics of a shameful past, to be erased behind painted cement or cheap tiles. This is to forget that, in each built space, there was a fine understanding of society, its hierarchies, its bonds of solidarity.

The paradox is cruel. While the world is rediscovering the virtues of sustainable architecture, Africa continues to import energy-intensive models, often unsuited to its climate, its uses, or its resources. Where we should be drawing on vernacular genius to design the cities of tomorrow, we are imitating glass facades in neighborhoods lacking water, or soulless towers in suffocating cities.

Doing justice to African architecture is therefore more than an exercise in memory. It is a contemporary emergency. It means relearning how to build with the place, with time, with the men and women who live there. It means rehabilitating knowledge, not to freeze it in a museum, but to make it the raw material of a rooted modernity.

Because our cities don't need an imported style to be modern. They need soul, meaning, and that intelligence of the territory that our ancestors, without diplomas or cement mixers, mastered better than many of today's architects.

Commentaires (15)

Nous devons effectivement privilégier une architecture adaptée à nos besoins plutôt que d'importer, sans plus y réfléchir, des modèles qui conviennent à ceux qui les ont pensés

C'est vrai en architecture comme dans d'autres domaines d'ailleurs

Aucune cohérence dans les villes, c'est un soupou kandia vu du ciel. Les villes sénegalaises sont vilaines.

A croire qu'il n'existe pas de ministère de la ville ou des collectivités locales.

Ce sont des articles comme ça qu'il faut écrire et transmettre à qui de droit car réfléchis utiles.

Merci beaucoup pour cette réflexion et bonne continuation,il faudrait peut être transmettre aux architectes au ministère de l'urbanisme au 1er ministre et réfléchir à sa mise fn œuvre surtout pour les projets de logements sociaux dans certaines zones car Dakar et les agglomérations c'est raté !!!

Une Oeuvre est une Oeuvre. Et un Genie un Genie.

Nos constructions ne sont pas du tout adaptées à notre environnement

Thiey Aïcha Fall ! moom daal ses articles se boivent très souvent, pour ne pas dire tout le temps, comme du petit lait rrek.

primitif inculte c'est doux !!

https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-58913094

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter ou TikTok pour l'afficher automatiquement.